Songwriting

How Important is Honesty in Songwriting?

A recent blog from ReverbNation titled, “Why Honesty is Important in Songwriting” got me thinking about this. And my title isn’t really honest (to tell the truth) because I believe, as did the writer of the article, that honesty is very important. For me, the question is more about how, as a songwriter, you can achieve honesty. One way is physical.

A recent blog from ReverbNation titled, “Why Honesty is Important in Songwriting” got me thinking about this. And my title isn’t really honest (to tell the truth) because I believe, as did the writer of the article, that honesty is very important. For me, the question is more about how, as a songwriter, you can achieve honesty. One way is physical.

A few years ago, I was co-leading a retreat with my Crafting Songs partner, Chris Alexander. Our group was made up of high school students. Their developmental challenges went beyond songwriting, for sure. It is tough being an adolescent. But something that struck Chris and me was the cleverness of the lyrics and the way the writers concealed themselves behind that cleverness.

Some people think that irony is the bane of the Millennial generation. I don’t know about that. Composing songs made of an avalanche of words, images, ironic commentary is a trap for many at any age. But I did notice that being “safe” behind the clever irony was very much a thing in this group. Something that went along with that: a tight-lipped presentation. These young singers were keeping their mouths shut, literally, as if to leave one’s throat exposed for too long left one vulnerable.

We’ve probably all read that years ago the act of covering one’s mouth during a yawn or a sneeze was not so much about hygiene. It was about keeping the devil from jumping down your throat. That instinct, in a different frame, seemed to be at work with these kids. Don’t let anybody in. Don’t leave yourself open to hold a note longer than a quarter of a measure.

We’ve probably all read that years ago the act of covering one’s mouth during a yawn or a sneeze was not so much about hygiene. It was about keeping the devil from jumping down your throat. That instinct, in a different frame, seemed to be at work with these kids. Don’t let anybody in. Don’t leave yourself open to hold a note longer than a quarter of a measure.

When I challenged them to do just that, they listened. The first evening thereafter when we shared the work of the day, suddenly there were whole notes. Tied whole notes. Those kids were writing choruses that sang rather than muttered. They felt the difference themselves. They applauded each other. They rewarded each other’s newfound vulnerability. The work that week got better and better.

Seeing that result changed my own songwriting. I approached my choruses differently. I realized, as had the kids, that holding out notes invites others—not to critically “jump down your throat,” as the saying goes— but to join with you. Songs become more communal when there is opportunity, invitation for others to join. And isn’t building community what songs and what singing are all about?

Oh, Johnny Crewcut

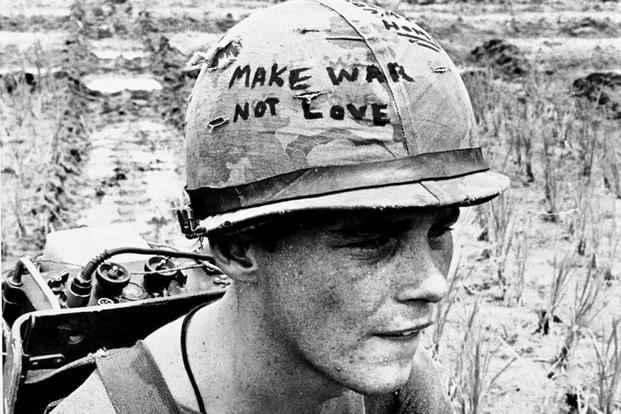

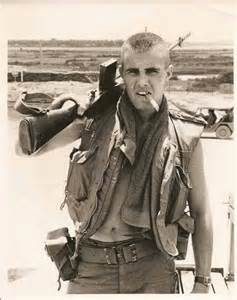

I have a song called “Johnny Crewcut” about young men I grew up with and went to school with in Gill, MA, and who weren’t as lucky as I was, as I am.

The character is a composite of two or three individuals, but the reason for the title is the real central figure, John Zywna, who was a couple or three grades older than me. In high school, he became a star athlete—a football hero. Then he went to Vietnam. And a friend from back there told me he had been killed.

I wrote the song as a poem first after a drive down Main Road, Gill on my way to the airport one summer. I took the same route the school bus took every morning. That took me by the Zwyna’s house and cow barn, then the Tyler’s on the other side of the road. Both families figure in the title character of the story when it became a song one summer after another drive through my old hometown.

I wrote the song as a poem first after a drive down Main Road, Gill on my way to the airport one summer. I took the same route the school bus took every morning. That took me by the Zwyna’s house and cow barn, then the Tyler’s on the other side of the road. Both families figure in the title character of the story when it became a song one summer after another drive through my old hometown.

Last week, I went to an open mic in Brattleboro, VT. I had just gotten into town and called The Marina to ask if they still had an open mic and if so when it was. The woman said, “We do!” I asked, “When is it?” And she said, “Tonight!” “What do I have to do to get on the list?”

She gave me the 9:20 slot. Late, but I had dinner plans. I arrived about 8:30, as the host and the house band were roaring through their set. They were an interesting four-piece: two guitars, bass, and trumpet? The odd thing was it actually worked. The trumpet and one guitarist trading licks was amazing. And not just for Brattleboro on a Thursday night.

Before it was my turn to go on, I brought my guitar into the hallway outside the restrooms to warm up. A guy went by me into the men’s room, looking over his shoulder as he did. I moved out to catch the guy before me finish out his set. The bathroom guy plus another couple were heading out. The BG said, “That sounded great. I wish we could stay.” I said, “So stay.” They left. But ten minutes later, they came back.

I plugged in, did an opening song written in the 1850s (I called it a ‘50s tune) that went over well. Then I introduced “Johnny Crewcut.” I said pretty much what I did above. I said “Gill,” because no one has ever heard of it outside of about a fifty-mile radius. I ended the way I usually do, the way I did above, by saying the song is for those boys who weren’t as lucky as me. Then I sang the song. There’s a link to a recording at the bottom of the page.

It begins with me in a rental car, an emigrant, come home to gloat and reminisce. I notice a few old landmarks. The second verse introduces Johnny in the past: “He grew up poor in a family of ten/Working all summer on that bottom land.” Many kids in my class worked summers picking tobacco or baling hay, or both. They bragged about how many levels—tiers—they could throw a hay bale. I always like the sound of that.

The third verse—half as long— is Johnny’s death in Saigon, imagined because no one has ever told me what happened. After an instrumental break, time breaks as well, and we’re back in the car, in the present. I had gone off Main Road, down by the Connecticut River where some of the most fertile soil in the Valley can be found. The road abandons the river a few miles from the center of town, and turns and climbs into a forest of White Pines higher on the old riverbank. The song ends honoring Johnny by remembering him, or more precisely, not forgetting him, which takes intention and will. Saying his name out loud. At the end, just his name, repeated: “Oh-oh, Johnny Crewcut.”

Again, it was well received. The crowd was small, but mainly musicians, so their approval meant something. I sang three more. Then the house band, sans trumpet, came back to close out the night.

Several people upfront told me afterwards that they lived in Greenfield, where I was born. They knew Gill. (Pause) But they didn’t know Johnny Crewcut. I said, “Well his ‘can-I-buy-a-vowel’ last name was ‘Zwyvna.'” They looked at each other. “Isn’t that Tracy’s name?” “Yes, but without the ‘v.'” “Oh,” I said, “I might have added that after someone in the audience once told me I’d left out a consonant.” But apparently, I hadn’t.

“Tracy” was Tracy Zwyna, their neighbor across the street, whose dog had recently gotten out and run over into their house. She could be “Johnny Crewcut’s” granddaughter, grand-niece, or whatever. But in that area, in that town, almost assuredly the same family.

That was strange and wonderful small-world stuff, for sure. That was the first time I had performed the song within a few minutes’ drive of the setting in my childhood. That was powerful in itself for me.

But it felt like something else to me. If there is magic in names, and if speaking a name is summoning a spirit, then I think I had an answer that night. “Oh, Johnny. Where are you now?”

Here. Right here.

Here’s the link I promised.