When I was just finishing college, I learned that Jonny had drowned in a white-water canoeing accident. I heard that his body had not been recovered, but that there was no chance that he could have survived, given the circumstances. I was stunned, not only by the information and the sense of loss that accompanied it, but also by the fact that I had recently received a letter from him, eagerly reporting this plan to attend a camp in Ontario, and closing with a sentence that reverberated in my ear: “Don’t write after June. I won’t be here.”

Younger Jonny seemed a delicate, ethereal, young man. Gangly, though wiry and strong. He had a stammer, and began his sentences with “Ya-a-a-a-ah know . . .” as a space holder in conversation, because he learned that unless he asserted himself somehow, he might never get a word in. And being boys, we naturally dubbed him “Yah-no” in place of Jon. He accepted the name without objection. What else could he do?

He and I played all the pick-up sports together: tackle football, baseball, basketball. We played army in the nearby woods, and went camping there, too. Sometimes the two of us went paddling on the lake near our homes, and once at least on the Connecticut River. I remember once I leaned too far over the gunwale of the canoe we were maneuvering through late spring ice on Shadow Lake. I felt myself start to go overboard toward the freezing water. But Jonny grabbed the back of my coat and held me in. That was the extent of my canoeing accident.

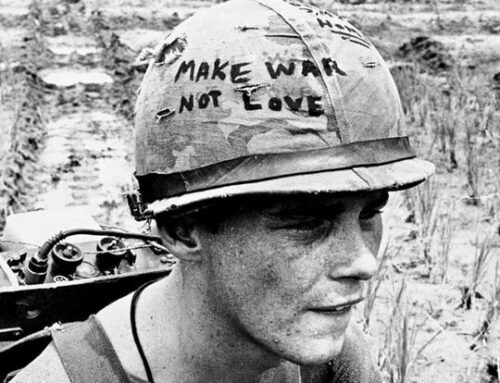

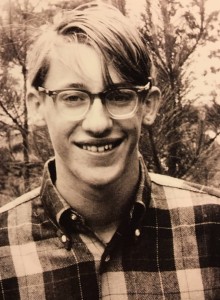

Recently there was a reunion of “Fac Brats” like me who spent a significant portion of their childhood at a school in Western Massachusetts where our parents were teachers. I didn’t attend, but was happy to get posts with photos on Facebook. One included two shots of Jonny: one around 18, the time of his death, and another from when I knew him best—about 10 years old. They were posted by his sister, Kathy, with a simple memorial attached. The older one is above. Here’s the later.

Recently there was a reunion of “Fac Brats” like me who spent a significant portion of their childhood at a school in Western Massachusetts where our parents were teachers. I didn’t attend, but was happy to get posts with photos on Facebook. One included two shots of Jonny: one around 18, the time of his death, and another from when I knew him best—about 10 years old. They were posted by his sister, Kathy, with a simple memorial attached. The older one is above. Here’s the later.

As a result, she and I got in touch after probably more than 50 years. From her I learned that Jonny’s body had been found about a month later. A local Native American fishing guide had told authorities that if the river was going to give up the body, it would be in a certain spot. And there it was. There he was. His watch was still working.

I wrote a poem, an elegy, for Jonny back then. I have reworked it many times through the years. I’ve known that to be an indication that his death was significant and getting the tribute right was important. Just before writing this, I revised it again. I know I’m looking for some emotional closure that a poem may never bring. I imagine a transformation for him that I hope could somehow be real.

Around the time I was first writing the poem, James Taylor famously wrote, “I walked out this morning, and I wrote down this song/I just can’t remember who to send it to.” Now at last, I’ve had someone to share my poem with—Kathy. I’m hoping it matters to her and to her brother Peter. Her mother, too, if she’s still living. I know they, too, are still seeking closure for this unthinkable loss. So bear witness to Jonny’s life and death, and to our grief, still somehow fresh after all this time.

The Fey

For Jonny, lost in Canada

Together, we never rode loud water.

As children, we dipped oars in lakes’ piney silence,

or stroked the river’s moonlight glide.

We called you “YAH-no” then

with the affectionate cruelty of boys, playing

on your name, and on that stammering sound you made.

Often you were silent, two fingers sucked

between your lips, your words jammed in your throat,

your thoughts tangled somewhere inside.

Years later, when you moved, we lost touch.

But I still have your letter, sent that March:

“My brother and I—canoeing camp—northern Ontario. . .”

I pictured white water, filling day and night with sound:

a kind of silence where you wouldn’t have to speak.

Closing, you said, “Don’t write after June. I won’t be here.”

That was all—the last of you: Your craft capsized,

your body lost; your voice—that welcome, fluted stumbling

swept away in rapid clamor.

Now sometimes, the river calls, and when I go,

I always hope to find you: rising like a sea-god, Jonny,

and roaring like the Colorado.