“Jefferson Airplane”? Not exactly a contemporary reference, I know. But the confluence of several streams of consciousness has me writing this. And, as my wife will tell you, I spend a lot of time in the past.

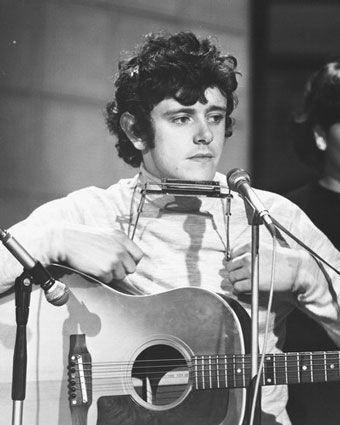

Donovan

Many years ago, in high school, I discovered Donovan. If you don’t know who that is, I forgive you. Donovan Leitch was, in a manner of speaking, the British Dylan (although I have many British friends who will probably eviscerate me for that. They know that Dylan is the British someone-else.) But you may remember a pair of hits from oldies stations or movie soundtracks. Sunshine Superman or Mellow Yellow? What about an earlier folky tune, Catch the Wind? Season of the Witch? Anyone? Bueller?

In any case, I listened to Donovan an extravagant amount.

At that same time, I was attending a Massachusetts boarding school, where my roommate was from California. That was amazing in itself. But more important, he became the source of a lot of great music. Some of it from England after a vacation trip to London. More from the San Francisco Bay area, where he lived when not sharing a third-floor dorm room with me.

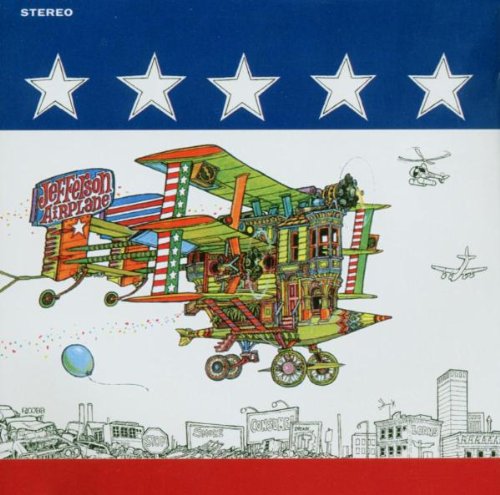

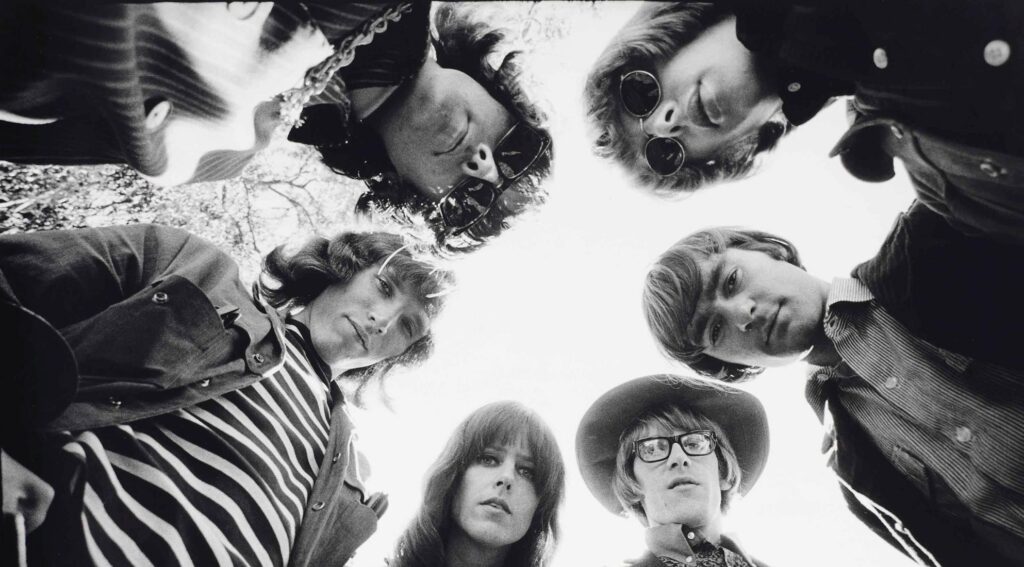

It was fall of 1965 when we began rooming together, and June 1967 when we graduated, which you have to admit was a pretty amazing time for music. Among all the memorable artists of that time, Jefferson Airplane ranked high. It may be hard to imagine now, but they were once the “it” band. No Top-40 hits after Somebody to Love and White Rabbit, but amazing countercultural popularity. They were on the cover of Life magazine. They were on Ed Sullivan, and more significantly, the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour! They were at Woodstock—one of the main acts! All while singing about a revolution in a real way, not as an intellectual abstraction.

The Airplane

In the first months of my familiarity with The Airplane (as I learned to call them, while feigning prep-school boredom), I happened to notice that toward the end of Donovan’s song, Fat Angel, instead of singing the refrain, “Fly trans-love airways, gets you there on time,” he substituted, “Jefferson Airplane” for trans-love airways. As I write this now, more than fifty years later, it seems pretty obvious that Donovan meant the reference every time. Only once, he made it overt.

Small potatoes? Not to me! Suddenly an amazing inter-dimensional culture warp occurred. This British singer was somehow aware of, was a fan of this then-still-obscure San Francisco band! It was all coming together!

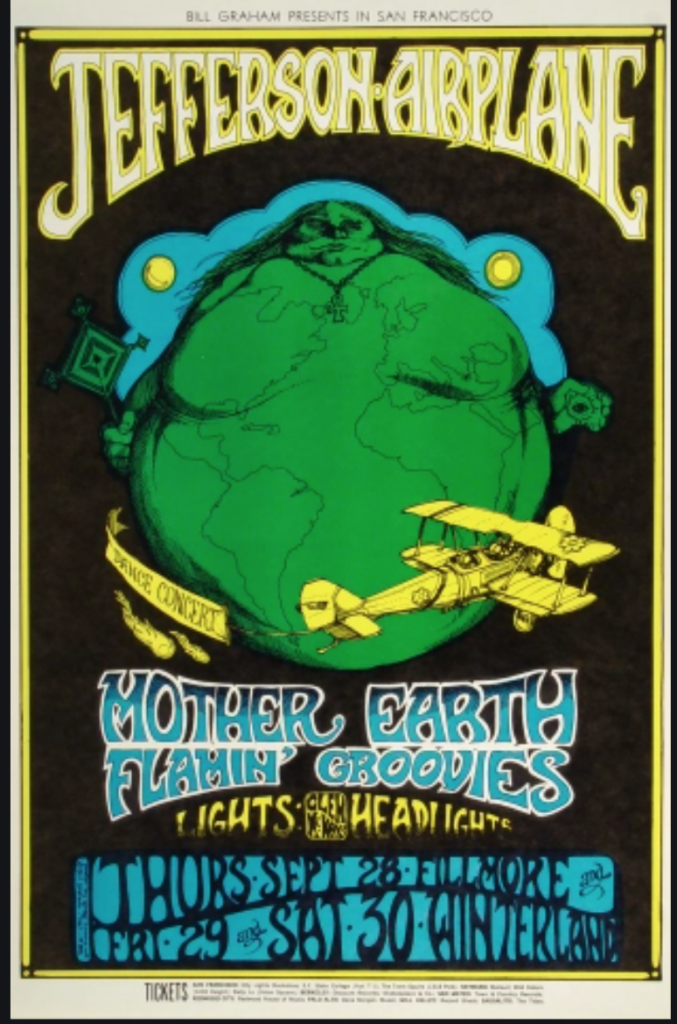

Winterland Ballroom

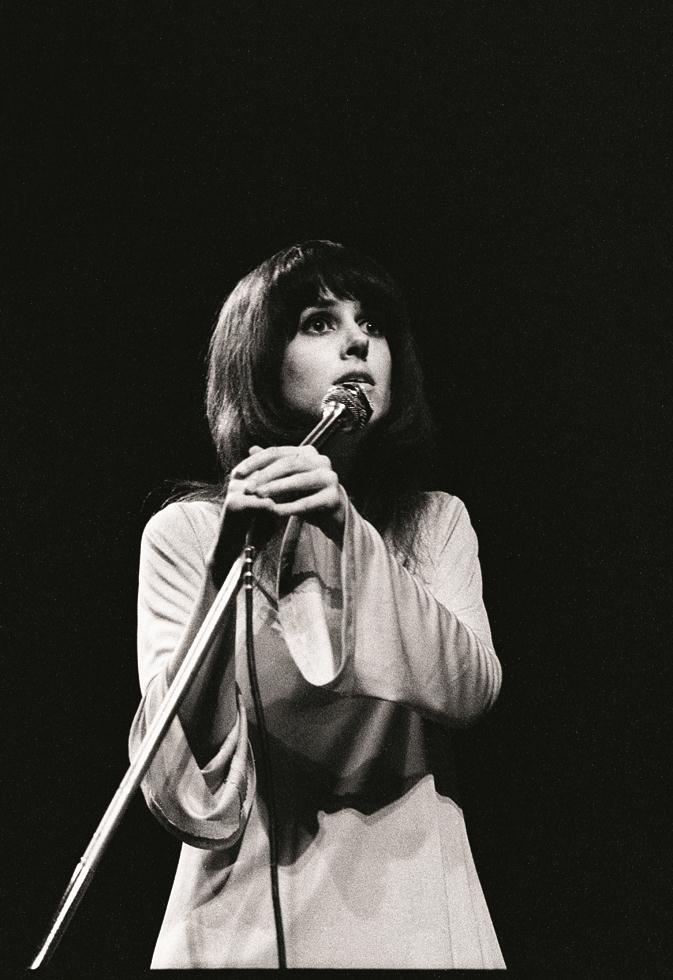

Maybe for me, this was the beginning of a sense of the coming counterculture with which I would soon be much better acquainted. I went to college in the SF Bay Area. For my freshman orientation there, I went to Winterland Ballroom, a former skating arena, now a concert hall in San Francisco. The Airplane was headlining. Still technically the Summer of Love, fame hadn’t completely overtaken the scene. There was no “backstage” where the stage was located. So the band exited through the audience to get to their dressing room. As the band passed by, in my rural-Western-Massachusetts, star-struck stupor, I asked Grace Slick a question. A stupid, embarrassing question, true. But she answered me, if only to direct me to another band member who had written the song I asked about. But Grace Slick had spoken to me!

Truth be told, I felt a kinship with Grace. She, too, was a preppie (although I didn’t learn all about that until later) who went to a prestigious girls’ school in Palo Alto. She went to Finch with one of Nixon’s daughters and was on her way to becoming a model—beautiful, yes, but acerbic and whip smart. The kind of girl I might have dated back in school in Massachusetts. One who would have endured me for a date or two, then disposed of me. I would have deserved it.

That is achingly apparent in my early attempts to understand the music she wrote and performed with The Airplane. When I first heard the climactic chorus of White Rabbit, for example, instead of the iconic line, “Feed your head!” I heard, “Keep your head.” (Yes, I was a good son—a well-behaved young man from Western Massachusetts. Well, I learned.)

reJoyce

Right about now, I’m itching to play a track from After Bathing at Baxter’s, the band’s third album, for my wife. She will roll her eyes, shake her head. She is sometimes exhausted by my preoccupation with the past. It’s amazing I don’t walk into things, according to her. And by my asking her to listen to music I find interesting—true for me, for her, not so much. But she loves me anyway, thank goodness. She will decline the offer.

So listen: reJoyce is a piece Grace wrote and performs on piano as well as with her voice. She’s accompanied by bass, a little subtle drumming, and some overdubbed woodwinds. But it is a largely acoustic piece: part Ravel, part jazz, part snake charmer. I would bet that almost no one outside of a small circle of former Airplane fanatics (Richard, are you there?) would remember it. But it is a masterpiece of weird, convoluted, evocative lyrics (as the title suggests, there are many references to James Joyce’s Ulysses), rhythmically and sonically sophisticated piano, and of course, Grace’s voice.

Sometimes I think that her approach to music was from the perspective of a lead guitarist—and I’m not the first to think that, I know. She sometimes finds responses to calls that have never been made. As a consequence, her style was magical, unique, and sometimes a little weird. And The Airplane, live, were often deafening. (Once, I saw Grace onstage with big Koss headphones—a monitor or earplugs? Both?) And that volume removed the piano from their stage sound early on. Some subtlety went by the boards.

It’s A Wild Tyme

But listening again now (and yes, my own headphones are on) to reJoyce, I almost weep. This happens to me. I’m never sure why. But I know it has a lot to do with memory, with the perspective of fifty years on that time of my life. Maybe a little bit with the excesses and failures of a time that seemed to presage such positive change. On one song from that same album, Grace sings, “It’s a wild time. I’m doing things that haven’t got a name yet.” That statement seems so true and yet so far away. Then the last line of reJoyce: “All you want to do is live, all you want to do is give/But somehow it all falls apart.” Kind of an epitaph.

I guess it did fall apart. But if I put the headphones on, though the time has passed, I can fly Jefferson Airplane again.